In a blog post on The Conversation, Jordan Gaines Lewis extols the virtues of simplicity, both as a viewer and presenter:

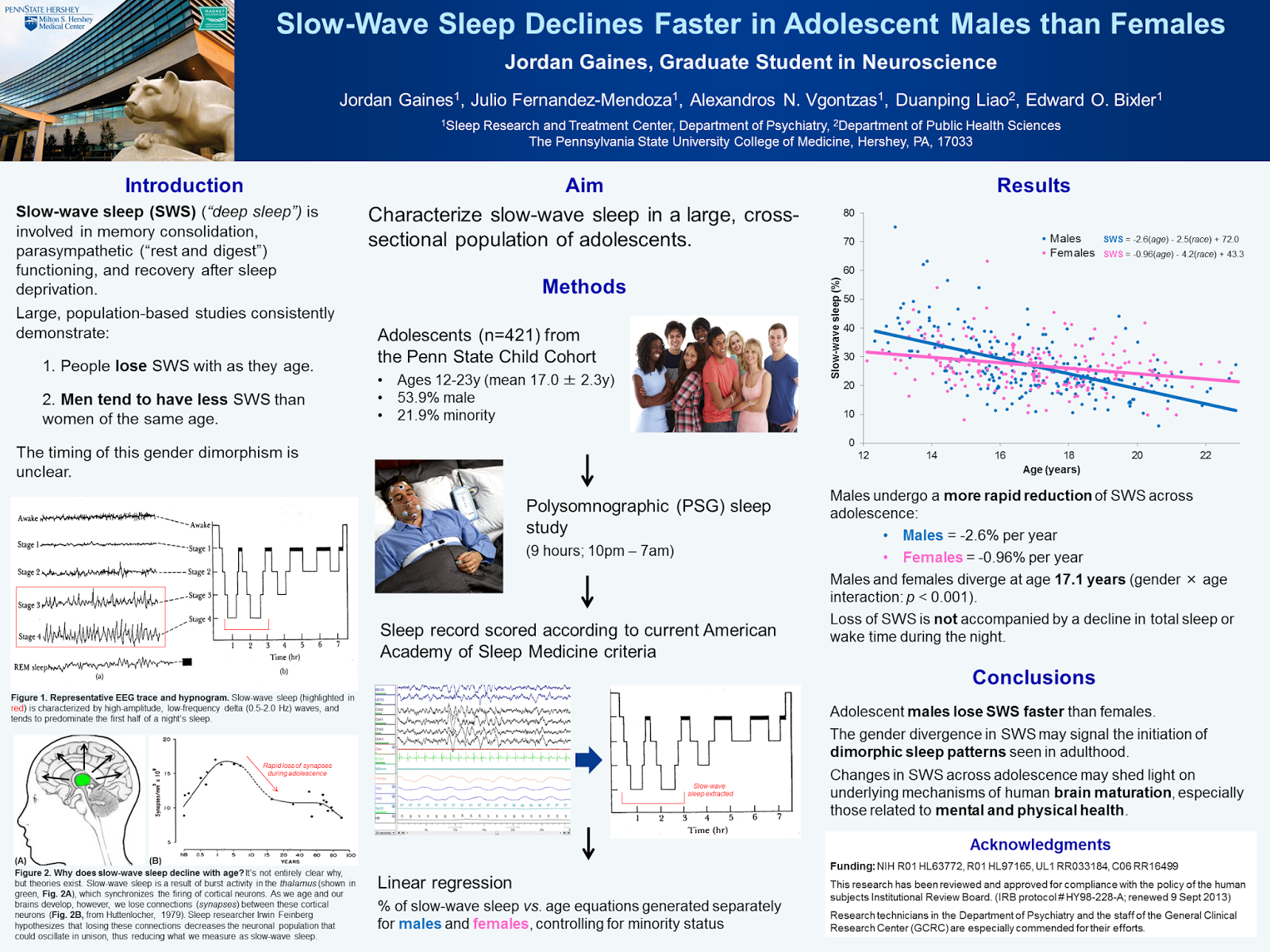

I was struck by Jordan’s description, and asked if we could see an example of her work. She was kind enough to send one of her examples. Click to enlarge!

Jordan’s poster is indeed simple: this poster has one result. It succeeds in that anyone looking at it will think they can get the main messages of the poster in a few minutes.

I asked Jordan to talk about this poster, and I was delighted she replied with much more than I could have reasonably expected:

Because I am a tinkerer, though, I thought I would see if there were some things that might make things even better. Jordan described her style as “blocky,” so I start, as I often do, by removing boxes, first around the main text blocks:

Then I pulled out the boxes around the inner images:

Then I went in and tried to harmonize the text, by making a little more room around it, and making the sizes more consistent. I also removed the white fill in some text boxes to allow the pale blue background to come through.

Then a few more text changes, notably to the title. And I got rid of that last box in the figure legend.

Also, forget the wordy background information, paragraphs and long conclusions – when I look at your research poster, I’m only looking at the title and figures. ...

Nowadays, when I design posters or oral presentations, I aim to do the same thing regardless of whether I’m introducing my work to scientists or non-scientists. My research posters, in fact, are almost laughably simple. Well under 200 words, with large, blocky figures, at first glance they may resemble a high school science project – certainly not a typical graduate student’s work at an international conference.

But the human brain is attracted to simplicity. Since applying what I’ve learned from being a science communicator, my conference poster experience has completely changed. I’m frequently bombarded by a non-stop stream of scientists from all different fields, never having more than a free minute or two to sneak a swig of water. The best part is that because they understand what’s on the paper, our discussions can go deeper.

I was struck by Jordan’s description, and asked if we could see an example of her work. She was kind enough to send one of her examples. Click to enlarge!

Jordan’s poster is indeed simple: this poster has one result. It succeeds in that anyone looking at it will think they can get the main messages of the poster in a few minutes.

I asked Jordan to talk about this poster, and I was delighted she replied with much more than I could have reasonably expected:

A few years ago, when my first scientific conference was around the corner, I couldn’t wait to make a poster. I was awed by those with complex titles, long-winded methods, and tons of detailed graphs. To me, this style reeked of intelligence, complexity, and months of hard work. I wanted to show off, too.

…until I went to my first scientific conference, and I found myself avoiding these types of posters like the plague.

We humans like simple things. And especially in a hall filled with hundreds of posters (and ten times that many people milling about), our eyes want to focus on the least chaotic item in the room and find comfort there.

My style of designing posters changed dramatically after I participated in Penn State’s Graduate Exhibition last year—a school-wide celebration of graduate work in all disciplines, from theoretical physics to visual arts. Our posters are judged by professors, students, alumni, and volunteers from the Penn State community who come from all different backgrounds and areas of expertise. Our work must appeal to (and be understandable by) everybody.

Distilling a year’s worth of work into an easy-to-understand poster was not a cakewalk. Eventually, I settled on a single figure, a flow chart to visualize my methods, and an image to complement my background information. The text was large and the colors were simple.

As I spoke, I found it easy to carry my judge along the way while pointing out images and figures. This experience was a revelation to me: the poster is not the centerpiece. Rather, it’s the accessory to the story that comes out of the expert’s mouth.

Despite this positive experience, I was a bit nervous to re-use this simple poster a few months later at an international conference specific to my field of study. As I hung it up in the morning, it looked laughably simple next to the surrounding posters.

But when the poster session time rolled around, attendees were drawn to mine like flies to honey. To me, the best part was that since the methodology and results were so clear from the poster, I didn’t have to waste our time by answering clarification-type questions. Instead, our conversations could go deeper—about further experiments, implications for the work, and how my findings relate to the field at large.

The goal of your poster is to inform, not impress. Teach, not overwhelm. It’s harder to cut down words than it is to copy/paste from the Methods section of your latest publication.

Poster-making is truly an art form—some people are naturals, and others need assistance even after decades of presenting their work. I’ve still got a lot of learning to do myself, and I can’t wait to prepare for my next scientific conference.

Allot yourself a bit of extra time to design your next poster. Have a layperson take a look over it before you print it. Give simplicity a try. I have a feeling you’ll find yourself having more quality discussions with more scientists at your next meeting.

Because I am a tinkerer, though, I thought I would see if there were some things that might make things even better. Jordan described her style as “blocky,” so I start, as I often do, by removing boxes, first around the main text blocks:

Then I pulled out the boxes around the inner images:

Then I went in and tried to harmonize the text, by making a little more room around it, and making the sizes more consistent. I also removed the white fill in some text boxes to allow the pale blue background to come through.

Then a few more text changes, notably to the title. And I got rid of that last box in the figure legend.